- Home

- Louis Sachar

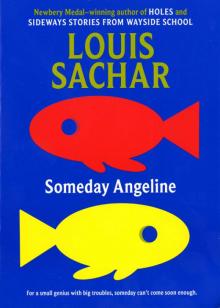

Someday Angeline

Someday Angeline Read online

LOUIS SACHAR

Someday Angeline

Someday Angeline, a good story

with lots of funny jokes,

is dedicated to everyone who can

tell whether or not a book is any good—

by smelling it.

Nobody tried to figure out anymore how Angeline knew all the stuff she knew, the stuff she knew before she was born. Instead, they called her a name. They called her “a genius.” And even though it really didn’t explain anything, everybody considered it a satisfactory explanation. Like the way she always knew what tomorrow’s weather would be. “How does she do it?” someone might ask. “She’s a genius” they’d be told, and somehow that would explain it. And that way, nobody ever had to really try to understand.

Table of Contents

Prologue: Nina’s Untrained Ear

One: How Abel Smells

Two: A Goat with Two Heads

Three: A Goat with One Head

Four: No Tomatoes

Five: Mr. Bone

Six: Secretary of Trash

Seven: The Balance of the Whole

Eight: Mr. Bone Let Me Feed Her Fish

Nine: Garbage

Ten: Fish

Eleven: Mrs. Hardlick’s Triumph

Twelve: More Fish

Thirteen: No Going Back

Fourteen: Mr. Bone Is on the Phone

Fifteen: Otherwise Known as Mr. Bone

Sixteen: Crazy Driver

Seventeen: Different Directions

Eighteen: Where’s Cool Breezer?

Nineteen: The Only Way to Find Her Is to Tell Her a Joke

Twenty: Spoon and Prune

Twenty-One: Pretty Feet and Green Her Eyes

Twenty-Two: You Never Know

Also by Louis Sachar

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Nina’s Untrained Ear

“Octopus,” said Angeline Persopolis.

She was only a baby. It was the first word she ever said, which was why it was preposterous.

Nina, Angeline’s mother, was the one who had heard it. Her big eyes opened even wider. “Abel!” she screamed with delight. “Abel! Angeline said something. She said her first word! Abel!”

“Wha’d she say?” asked Angeline’s father as he rushed into the living room, where Angeline lay in her crib.

Nina suddenly looked very confused.

“Come on, Nina,” urged Abel, “what did she say?”

Nina looked oddly at her husband. “She said…octopus?”

“Octopus?” questioned Abel.

They turned and looked at Angeline, who lay peacefully sucking her thumb.

Abel called the doctor because, well, he didn’t know what else to do. It was she, the doctor, who said it was “preposterous.” She told them that they had absolutely nothing to worry about. She said that Angeline was only making simple baby noises—“ock” and “tuh” and “puss”—and that it was just a coincidence that it had happened to sound like “octopus” to Nina’s untrained ear.

Angeline’s parents were satisfied. They realized it had to be a coincidence because, after all, Angeline had never seen an octopus, and they couldn’t remember ever saying “octopus” in front of her. In fact, they couldn’t remember ever saying “octopus” at all.

Okay, fine. However, to this day Angeline remembers saying “octopus.” She is eight years old now. She has big green eyes like her mother’s and jet black hair like her father’s. And she remembers lying in her crib, in her soft pink blankets, peacefully thinking about the ocean, and the fishes, and especially about the funny-looking creature with eight legs.

There are some things you know before you are born. As Angeline grew up she seemed to know a lot of things that couldn’t be explained any other way.

When she was three, her mother, Nina Sandford Persopolis, died.

And then again, there are some things you never know.

One

How Abel Smells

Angeline lay on the floor of the living room with her feet up on the sofa, reading a book. The living room was also her bedroom. The sofa folded out into a bed.

It was a book about a sailor who was in love with a beautiful lady who didn’t love him back, which was why he became a sailor—to forget her. Only he couldn’t forget her, but he was an excellent sailor and he fought a pirate with one eye.

Nobody tried to figure out anymore how Angeline knew all the stuff she knew, the stuff she knew before she was born. Instead, they called her a name. They called her “a genius.” And even though it really didn’t explain anything, everybody considered it a satisfactory explanation. Like the way she always knew what tomorrow’s weather would be. “How does she do it?” someone might ask. “She’s a genius” they’d be told, and somehow that would explain it. And that way, nobody ever had to really try to understand.

She heard her father outside the apartment door. She bent the page in her book to mark her place and jumped up to greet him as he opened it.

“Don’t hug me until I take a shower,” he said, pushing her away. “I smell like garbage.”

“I like the way you smell,” said Angeline.

“You like the smell of garbage?” asked Abel.

“I do,” said Angeline.

She watched him walk into the bathroom and almost immediately she heard the shower running. “I bet he can take off his clothes faster than anyone in the world!” she thought.

He worked for the sanitation department. He drove a garbage truck.

In an odd way, he was afraid of Angeline. He remembered the time they went into a music store where she sat down and played the piano without ever having had a lesson. Everybody in the store stopped and listened to her. It was so pretty it scared him. He hadn’t taken her back there since.

More likely, he wasn’t as afraid of her as he was afraid of himself. He was afraid he was going to somehow blow it for her. “How’s an idiot like me supposed to raise a genius?” he often wondered. Probably if they didn’t call her that name, a genius, he wouldn’t have been half as scared.

He put on his pajamas and robe. It wasn’t even six o’clock but he was already dressed for bed. He never went out at night. He hadn’t gone out for over five years, not since Nina died. He stepped into the living room. “Now you can hug me,” he said.

Angeline hugged and kissed her father. “I liked the way you smelled before better,” she told him.

She followed him into the kitchen and watched him cook dinner. “Tomorrow, will you take me on the garbage truck with you?” she asked.

He sighed. “No,” he said firmly. “You know you don’t belong on a garbage truck. Besides, you have school tomorrow.”

“I hate school,” said Angeline.

“Why does she always want to ride on that filthy truck?” Abel wondered. He hated the garbage truck. The only reason he still worked at that stinking job was for Angeline, so that he could make enough money to send her to college someday. Someday buy her a piano. Buy her nice clothes because someday she was going to be a famous scientist, or a concert pianist, or President of the United States. “Someday, Angeline…” he thought.

“Well then, how about on a holiday when school’s closed?” she asked. “Then can I ride in the garbage truck?”

“Someday, Angeline,” he said.

Two

A Goat with Two Heads

Angeline was put in the sixth grade. They put her there because, well, they had to put her somewhere and they didn’t know where else to put her. They put her in Mrs. Hardlick’s class and that was probably the worst place to be put. She sat at the back of the room.

She started to put her thumb in her mouth but caught herself. She was sma

rt enough for the sixth grade. She was the smartest person in the class, but she still did dumb things like suck her thumb. She knew Mrs. Hardlick hated it when she sucked her thumb. Sixth-graders are not supposed to suck their thumbs. She also cried too much for the sixth grade.

“Who was Christopher Columbus?” Mrs. Hardlick asked the class.

Angeline was the only one who raised her hand.

Mrs. Hardlick looked annoyed. “Somebody else this time,” she said and glared at Angeline. “It’s always the same people.”

Angeline lowered her hand. It wasn’t her fault she was the only one. She didn’t think Mrs. Hardlick should have been mad at her for raising her hand. It was everybody else’s fault for not raising theirs. But in her mind she could hear Mrs. Hardlick saying sarcastically, “It’s always everybody else’s fault, never your own.” As she thought this, her thumb slipped into her mouth.

Mrs. Hardlick told the class about Columbus. She said that Columbus discovered America.

Angeline knew that was wrong. How could Columbus have discovered America when there were already lots of people here when he arrived? She knew that America was actually first discovered by the first snail to crawl out of water and onto land. It was something she knew before she was born.

However, she tried to give both Mrs. Hardlick and Mr. Columbus the benefit of the doubt. “Maybe,” she thought, “from his own point of view Columbus discovered America.” But that didn’t seem true either because even after Columbus got here, he still didn’t know he was in America. He thought he was in India, which was why he called Americans “Indians.”

Mrs. Hardlick said that Columbus proved the world was round.

Angeline knew that was also wrong. If he really had made it to India, then he would have proved it was round because India was east and he sailed west. But he bumped into America first and he could have sailed to America even if the world was flat.

Besides, everybody knows the world is round before they are born. That’s why nobody is even slightly surprised when they first learn it in school.

These were the thoughts occupying Angeline’s mind when Mrs. Hardlick suddenly called her name. “Angeline!” she commanded. “Take your thumb out of your mouth right now!”

“Oops,” she thought as she quickly pulled it out.

“We don’t suck our thumbs in the sixth grade,” said Mrs. Hardlick proudly.

She heard some of the other sixth-graders snicker.

Mrs. Hardlick resented Angeline. She didn’t like having an eight-year-old kid in her class of sixth-graders. She especially didn’t like having an eight-year-old kid who was smarter than she, although Mrs. Hardlick would never admit that Angeline was smart. In Mrs. Hardlick’s mind, Angeline was a genius, which had nothing to do with being smart. It was more like being a freak, like a goat with two heads.

“Only babies suck their thumbs,” said Mrs. Hardlick.

Angeline felt ashamed. Even kids in the third grade, her age, didn’t suck their thumbs anymore. She felt like she was going to cry. “Oh, come on, Angeline,” she told herself. “Don’t start crying. Not now!” She cried way too much for the sixth grade. She even cried a lot for the first grade.

“Look, she’s crying,” someone teased.

She was not. It wasn’t true. But then, as soon as she heard that person say it, then, wouldn’t you know it, she did start to cry.

“She may be smart but she’s still a baby,” said someone else.

“She’s not smart, she’s a freak.”

“Angeline, don’t be a crybaby,” Mrs. Hardlick admonished her. “If you feel you must cry, go outside. You may come back in when you are ready to act like a sixth-grader.”

Still crying, Angeline walked outside.

“What a freak,” she heard someone say.

She sat down outside, next to the door. She was wrong. Mrs. Hardlick didn’t hate it when she sucked her thumb. It was just the opposite. Mrs. Hardlick loved it. The whole class loved it. They loved to put her down. And whether she realized it or not, that was why she cried. It wasn’t because they called her a baby or a freak; it was because they enjoyed it so much.

She bit the tip of her thumb and sniffled. She felt just like a double-headed goat.

Three

A Goat with One Head

At lunch, she sat by herself on the grass against a tree and ate a peanut butter and jello sandwich. She preferred jello to jelly with her peanut butter.

There was a boy also sitting alone not too far away from her. She watched him try to open his bag of potato chips. He pulled and pushed the bag in every direction until she was sure that all the chips inside had been smashed to smithereens. Still, the bag would not open.

She took another bite out of her peanut butter and jello and tried to keep from laughing. Besides crying too much, Angeline also thought she laughed too much. It wasn’t that she laughed a lot—just at all the wrong times. She thought watching the boy try to open his potato chip bag was the funniest thing she’d ever seen, but she didn’t want to laugh at him.

He bit the bag with his teeth and jerked at it with both hands. Nothing. Still holding it in his teeth and both hands, he vigorously shook his head.

She gulped down some milk, with her eyes fixed on the boy.

Suddenly the bag burst open, and Angeline instantly burst out laughing, causing milk to squirt out of her mouth. The potato chips exploded out of the bag and onto the ground. Angeline couldn’t stop laughing as she wiped the milk off her face with a napkin.

The boy stared at her. He still held part of the torn bag in one hand, part in the other hand, and part in his teeth. The potato chips were in little crumbs all around him.

Angeline did her best to stop laughing. She only managed to halt every other laugh. She hoped the boy wouldn’t hit her. She didn’t want to cry again.

But, to her surprise, the boy also laughed. It was a stupid, awkward laugh. He sounded like an embarrassed hyena. Then, seeing that Angeline was still watching him, he pretended to eat his empty bag of potato chips—not the potato chips, but the bag itself—as if that was all he ever wanted in the first place.

Angeline thought it was the funniest thing she’d ever seen.

Then the boy took his sandwich out of its plastic bag, threw it on the ground, and pretended to eat the plastic bag. Angeline couldn’t stop laughing. She watched as he poured the rest of his milk onto the dirt and pretended to eat the empty milk carton. She was hysterical.

At that moment there rolled past her a tennis ball, which someone had hit all the way from the baseball field. It stopped next to the boy who was so funny.

“Hey, Goon! Get the ball!” someone called.

The boy looked at the ball.

“Get the ball, Goon!”

He didn’t get it.

Philip Korbin, one of the kids in Angeline’s class, walked toward the boy. He was obviously disgusted that he had to walk so far and waste the recess when he could be playing baseball.

“Come on, Goon, throw me the ball,” he said.

“I’m eating,” said the boy, and he pretended to eat his milk carton again.

Angeline laughed.

Philip gave her a dirty look as he walked past her and got the ball himself. “What a goon,” he muttered, and started back toward the baseball field.

“Maybe if you didn’t call him a goon, he would have gotten the ball for you,” said Angeline.

“Shut up, Freak,” said Philip. He threw the ball back toward the field and ran after it.

“I hope you strike out,” said Angeline when she knew Philip couldn’t hear her. She didn’t know much about baseball except that the one time she got to play she struck out.

She finished her peanut butter and jello sandwich and washed it down with some milk. She still had some cookies. For the sake of his joke, the boy had thrown away his whole lunch. Angeline thought he looked hungry. “Do you feel like a cookie?” she offered. She took a sip of milk.

“I don’t kno

w,” said the boy. “How does a cookie feel?”

“Pppphhhrrrwwww,” laughed Angeline. This time the milk not only squirted out her mouth, it also squirted out her nose. She thought it was the funniest joke she’d ever heard.

The boy was shocked. He always told jokes, about a hundred a day, but he couldn’t remember the last time anyone had ever laughed at one.

Angeline couldn’t stop laughing. She didn’t want lunch to ever end. “What time does your watch say?” she asked him. She hoped there was a lot of time left.

The boy put his watch next to his ear. “My watch doesn’t say anything,” he replied. “It can’t talk.”

Angeline laughed again. She thought it was the funniest joke she’d ever heard.

Again the boy was amazed. He didn’t know what to think. Nobody ever laughed at his jokes. That wasn’t why he told them. He didn’t know why he told them, but it couldn’t have been to make people laugh because nobody ever did. Sometimes someone might say, “Ha ha, very funny, Goon,” but that was the closest anyone ever came to laughing. Mostly they just ignored him.

“I think you are so funny!” said Angeline when she stopped laughing.

The boy shrugged. “You’re the only one,” he said. He was really glad Angeline liked his jokes. It was just too bad that he had dumped all his lunch on the ground and didn’t even get the cookie that Angeline had offered. He was starving.

“What’s your name?” Angeline asked.

“Goon,” said the boy and then he laughed stupidly. “See, my real name is Gary Boone,” he explained. “So for a joke I combined my two names and I call myself Goon.” He laughed again.

Angeline didn’t laugh. She didn’t like being called “Freak,” and was surprised to hear that he had made up the name “Goon” himself. “Do you like it when people call you ‘Goon’?” she asked.

Gary shrugged his shoulders and said, “I don’t know.”

“Well, I’ll just call you Gary,” said Angeline. “I’m Angeline.”

Alone in His Teacher's House

Alone in His Teacher's House Holes

Holes Fuzzy Mud

Fuzzy Mud More Sideways Arithmetic From Wayside School

More Sideways Arithmetic From Wayside School Sideways Arithmetic From Wayside School

Sideways Arithmetic From Wayside School Pig City

Pig City Why Pick on Me?

Why Pick on Me? The Boy Who Lost His Face

The Boy Who Lost His Face Kidnapped at Birth?

Kidnapped at Birth? There's a Boy in the Girls' Bathroom

There's a Boy in the Girls' Bathroom Wayside School Is Falling Down

Wayside School Is Falling Down Stanley Yelnats' Survival Guide to Camp Green Lake

Stanley Yelnats' Survival Guide to Camp Green Lake Sideways Stories from Wayside School

Sideways Stories from Wayside School Super Fast, Out of Control!

Super Fast, Out of Control! A Magic Crystal?

A Magic Crystal? Someday Angeline

Someday Angeline The Cardturner: A Novel About Imperfect Partners and Infinite Possibilities

The Cardturner: A Novel About Imperfect Partners and Infinite Possibilities A Flying Birthday Cake?

A Flying Birthday Cake? Small Steps

Small Steps Wayside School Gets a Little Stranger

Wayside School Gets a Little Stranger Wayside School Beneath the Cloud of Doom

Wayside School Beneath the Cloud of Doom Is He a Girl?

Is He a Girl? Dogs Don't Tell Jokes

Dogs Don't Tell Jokes Class President

Class President Kidnapped at Birth

Kidnapped at Birth The Cardturner

The Cardturner Stanley Yelnats' Survival Guide to Camp Greenlake

Stanley Yelnats' Survival Guide to Camp Greenlake